What does climate change have to do with racism?

The killing of George Floyd brought issues of racial justice to the forefront of our national conversation. These conversations are extending beyond policing to the many other ways systemic racism impacts communities of color, including air and water pollution, climate change and health disparities.

The burning of fossil fuels contributes to climate change but also has a more immediate effect—pollution. The burden of this pollution falls more heavily on low-income communities and communities of color. Power plants, disproportionately located in Black neighborhoods, lead to higher rates of asthma and premature death. The Trump administration’s recent weakening of regulations governing power plant emissions are, therefore, likely to hit African American communities the hardest.

Respiratory ailments such as asthma put people at a higher risk for complications from COVID-19, contributing to death rates that are nearly twice as high for Black Americans than expected based on their share of the population. Dr. Adrienne Hollis, senior climate justice and health scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists, describes the intersection of racism, COVID-19, climate change and polluted air and water as a syndemic where multiple health crises intersect to exacerbate the suffering in vulnerable communities.

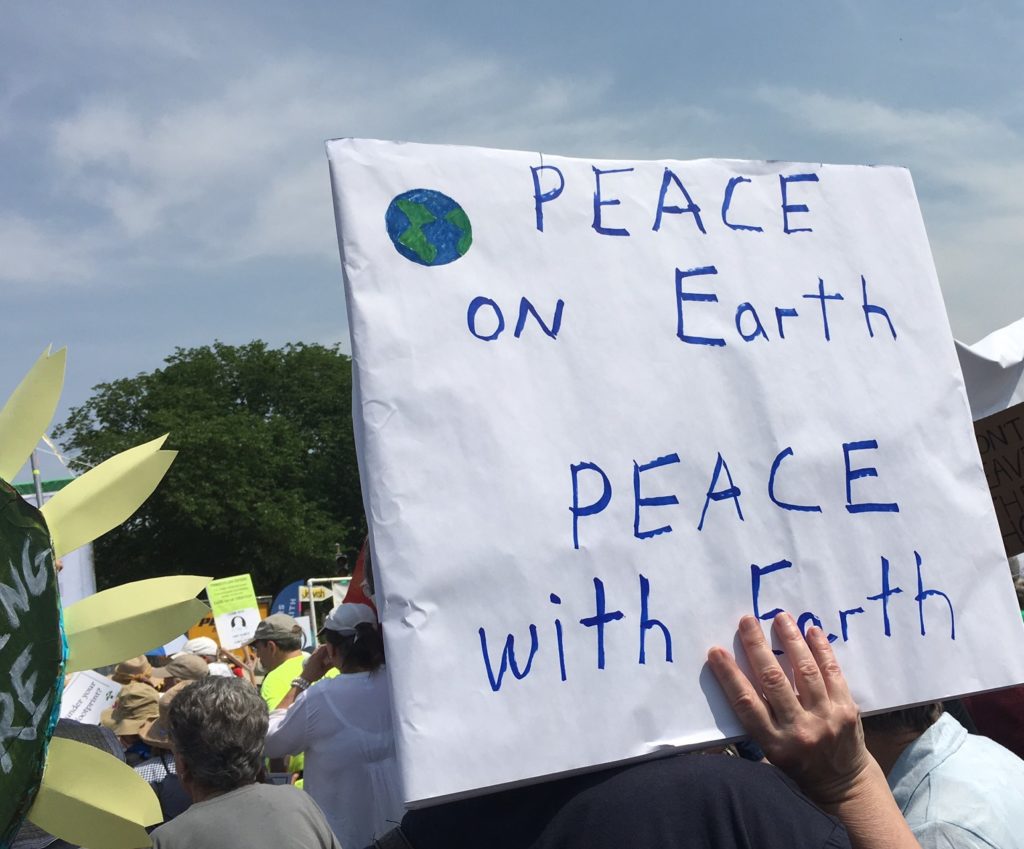

People’s Climate March in Washington, D.C., 2017. MCC Photo/Tammy Alexander.

While government regulations should be reasonable and not overly burdensome, they should protect people from corporations seeking to maximize profits while passing unseen costs onto surrounding communities. Regulations such as the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) have offered some protections, allowing local communities to raise concerns about how a new chemical plant or a new highway might affect their air and water. But a recent executive order will allow transportation and energy projects to bypass NEPA. “Gutting NEPA takes away one of the few tools communities of color have to protect themselves and make their voices heard on federal decisions impacting them,” said Rep. Raúl M. Grijalva (D-Ariz.), who chairs the House Natural Resources Committee.

Local communities could still protest the construction of a new power plant or pipeline that fails to adequately protect their clean air or clean water, but this avenue is closing as well. Several states have enacted new criminal penalties—up to six years in prison—for protesting the construction of oil and gas pipelines. Some have extended this to trespassing on, defacing or impeding the construction of any “critical infrastructure” including, in one state, telephone poles.

The military tactics used against racial justice protestors were all too familiar to those protesting construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline in 2016-17. Indigenous communities and their supporters raising concerns about water contamination and climate change were met with rubber bullets, dogs, water cannons and armored personnel carriers.

As Congress debates additional economic stimulus legislation, encourage your members to invest in clean energy and energy efficiency. Ask them to remember that preserving laws such as NEPA helps to ensure that local voices, including African American voices, are heard in policymaking. And continue to encourage them to protect lives and the right to protest by demilitarizing the police.

To care for God’s creation is to care for Black lives. The realities of systemic racism, climate change and COVID-19 require us to recognize that it is not business as usual. By working together we can root out injustice and build a better world.