Responding to the National Commission on Service

“As conscientious objectors, we believe Jesus commands reverence for each human life since every person is made in the image of God.” –From a letter sent by 13 Anabaptist groups in September 2019

When it was released on March 25, a report from the National Commission on Military, National and Public Service got little attention amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. The few headlines that did appear focused on the commission’s recommendation that women should register for Selective Service.

If it were to be implemented, the recommendation means that both female and male conscientious objectors to war would need to determine whether to register. But the commission made other key recommendations too, including some cases where the commission opted to keep things the way they are.

The commission, for example, does not recommend changing the harsh penalties that are in place for non-registrants. Currently men who do not register are subject to a $250,000 fine and up to five years in prison. While those penalties have not been actively enforced, non-registrants face other consequences, including an inability to get a driver’s license or federal student aid.

Rather than changing the penalties, the commission recommended a 30-day grace period during which people of any age could retroactively register without penalty. That could be useful for people who simply failed to register but does not help people who choose to not register as a result of conscience.

The commission also considered including a box on the registration form to indicate conscientious objection beliefs, but ultimately decided against it, saying there could be “possible confusion” if a registrant were to change one’s mind.

Commendably, the commission explores ways to create a “culture of service” in the United States and to significantly increase the number of people who serve. To do this, they suggest improving benefits for existing service programs (such as AmeriCorps) as well as creating a new “service fellowship” program. These changes could make it easier for people to do service regardless of their financial status.

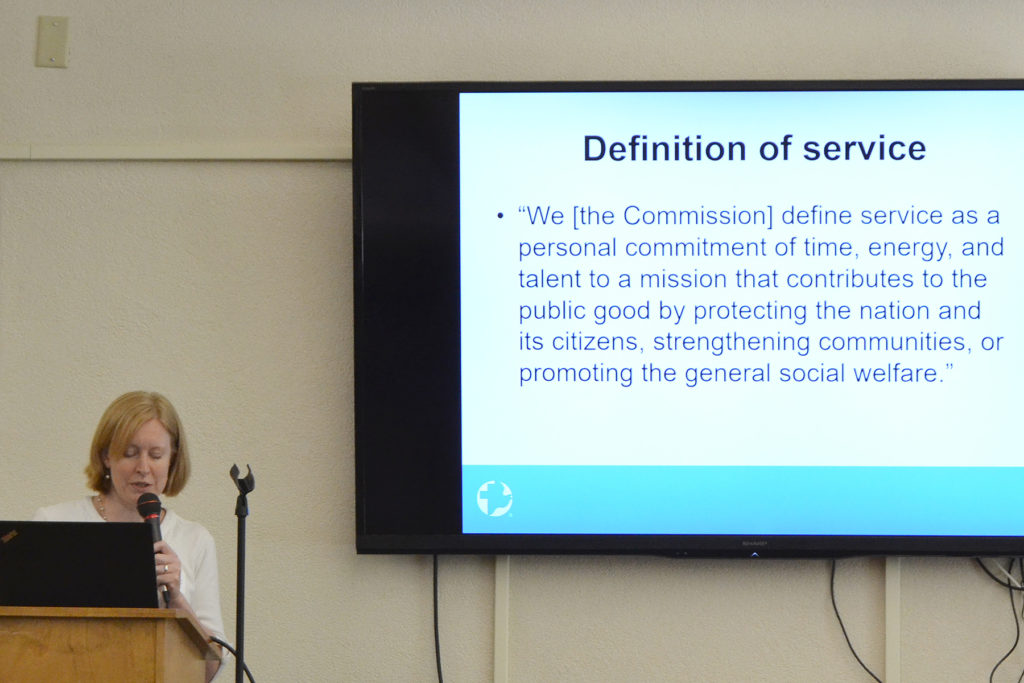

But the commission blurs together various forms of service: community service (what they call national service), government employment (public service) and the military, suggesting that recruitment and application processes be streamlined among them.

Rachelle Lyndaker Schlabach speaks at a June 2019 gathering of Anabaptist groups on the National Commission on Service. Credit: Cheryl Brumbaugh-Cayford/Church of the Brethren.

The commission wants to significantly increase the number of people volunteering for military service and suggests dedicating significantly more resources to military recruitment and advertising. The commission never addresses that the U.S. military’s budget already dwarfs that of any other federal agency; it certainly does not need more resources.

Congress will need to implement these recommendations for them to take effect. As they consider these proposals in the coming months, they need to hear from people who want to see our nation’s resources dedicated to peaceful ends. (Note that congressional offices continue to receive email and phone calls from constituents, even though they are working remotely.) Please consider contacting your member of Congress to let them know your perspective on the commission’s recommendations.