When Mennonites were banned

Written by Brian Dyck

In March 1922, Gerhard Ens, my step great-grandfather, made a trip to Ottawa from his home in Rosthern, Saskatchewan. He was part of a five-person delegation to meet the newly elected Liberal Prime Minister, William Lyon Mackenzie King. This was a follow-up meeting to remind King of the promise he made at a meeting 10 months earlier that if his party formed the government he would rescind an Order in Council from June 1919 that barred landing in Canada of “…any immigrant of the Doukobor [sic], Hutterite or Mennonite class.”[i] King kept his word and quietly rescinded the ban on these pacifist religious groups for entry to Canada.

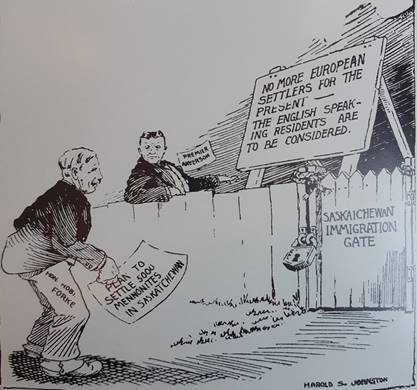

This cartoon, recently posted by the Mennonite Heritage Archives Facebook page, while created about a decade later, shows that negative attitudes towards Mennonites persisted. The “5000 Mennonites” referred to in the cartoon were refused entry into Canada, specifically Saskatchewan, despite the effort of the Canadian government under Prime Minister Mackenzie King to facilitate their immigration. This led Mennonite Central Committee to decide in January 1930 to make arrangements for them to go to Paraguay instead.

This ban on immigration had been put in place because of a negative attitude towards pacifist groups during World War I. John Wesley Edwards, Member of Parliament from the Kingston, Ontario area said “Whether they be called Mennonites, Hutterites, or any kind of ‘ites,’ we do not want them to come to Canada… if they are willing to allow others to do their fighting for them… We certainly do not want that kind of cattle in this country!”[ii] Edwards later went on to be Minister of Immigration and Colonisation in the Arthur Meighen government just before his party lost the 1921 election and Mackenzie King becoming Prime Minister.

The lifting of the ban cleared the way for the Canadian Mennonite Board of Colonization–with the help of the Canadian Pacific Railroad that provided travel loans for many–to help bring 20,000 Mennonites to Canada from the Soviet Union between 1923 and 1930, who faced famine, disease and violence as a result of the Russian Civil War.

Russia 1923. An interior view of a refugee train with a family of Mennonites from Schoenwiese, southern Russia (present-day Ukraine), travelling to Canada. (MCC photo/A. W. Slagel)

Through much of Canada’s history, groups like the Mennonites have advocated for their co-religionists to escape refugee-like conditions and settle in Canada. In return, these groups promised to make sure that these newcomers were settled and did not become a public charge. This practice seems to have shaped the refugee sponsorship provision in the 1976 Immigration Act which set the foundations of our current refugee sponsorship program.

While the 1976 Act mentioned refugee sponsorship, it did not go into details about what that might look like. The lack of details was severely tested in 1978 when Canadians began to see images on television of refugees fleeing Vietnam in boats. Canada had already resettled some Vietnamese refugees, but there was intense public pressure to do more. Many Canadians began to turn to the refugee sponsorship provision in the Immigration Act and as a result, the situation threatened to become too big for the government to manage.

At the January 1979 annual meeting of Mennonite Central Committee Canada, the issue of Southeast Asian refugees was raised. Participants urged MCC to remember the roots of Mennonites who fled persecution and were helped by MCC. MCC staff were instructed to work with the Mennonite denominations and organize a refugee resettlement effort. MCC was also directed to negotiate an agreement with the Canadian government to facilitate the resettlement of refugees with MCC constituents.

Shortly after that January meeting, Bill Janzen, MCC’s Ottawa office director approached the immigration department to begin negotiations. A spirit of collaboration developed during the discussions and on March 6, Bud Cullen, the Minister responsible for immigration came to Winnipeg to sign the first Master Agreement with MCC to facilitate the sponsorship of refugees. Within weeks, a number of other religious groups signed agreements modelled after MCC’s agreement, paving the way for a streamlined process of sponsorship approval. In the space of about 18 months, about 60,000 refugees from Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia were resettled in Canada. Slightly more than half, about 32,000, were resettled through sponsorship.

MCC and Government of Canada officials sign a private refugee sponsorship agreement in March 1979. (lr) Kirk Bell, Ken McMaster, Bud Cullen (Minister of Employment and Immigration), J.M. Klassen (MCC Canada Executive Secretary), John Wieler and Art Driedger. (MCC photo/Rudy)

Since 1979, more than 350,000 refugees have been sponsored to come to Canada. In that time, MCC with the help of hundreds of groups across Canada has resettled more than 13,500 refugees in communities in the five provinces where we work.

These two episodes—the Mennonite immigration from the Soviet Union in the 1920s and the negotiation of the first Master Agreement in 1979—are two key events that have shaped MCC’s historic involvement with people fleeing war and persecution. There are two important lessons that can be drawn from these two events.

First, it took advocacy to get this done. It involved working with elected MPs and government officials which relied on previous relationships and a level of trust and understanding that preceded the meetings. Gerhard Ens was chosen to be a part of this delegation in part because he was a member of the Saskatchewan legislature and through that had connections to the Liberal Party of the day. Later in 1979 when MCC negotiated the Master Agreement, MCC delegates, led by Bill Janzen, worked at building a good rapport with the government officials in charge of the program. That, according to the government negotiators, had a profound effect on shaping the agreement which included a focus on shared responsibilities.

Second, a shift in who MCC helps in resettlement. In 1921, Mennonites were able to use their connections and their good reputation with the new Prime Minister to allow the door to be opened for immigration of their co-religionists. Other groups were not so fortunate. Just a few years earlier in 1914, 376 passengers from India on board of the ship Komagata Maru were denied entry to Canada because of a law barring entry from anyone not making a continuous journey to Canada from their home country. Because of the distance from Asia, it was impossible for a ship to sail non-stop from India to Canada.

Southeast Asian families arrive at the airport in Winnipeg, Manitoba on May 2, 1979. (MCC photo/John Wieler)

With the negotiation of the sponsorship agreement in 1979, Mennonites had become part of a shift in thinking among many Christian groups after World War II regarding our response to not just our own refugees, but all fleeing war and persecution. As Don Peters, MCC Canada’s former Executive Director once said at a conference, “Our faith compels us to offer our resources to whom ever needs help.”

As MCC celebrates our centennial and moves into our second century, it will be important to continue to remember these stories, including the stories of those who were not welcomed, and continue to advocate for those who have been displaced. Everyone should to be able to either stay in their home community with safety and dignity or find a new home in our communities.

Brian Dyck is National Migration and Resettlement Program Coordinator for MCC Canada.

In September, we celebrate Mennonite Heritage week in Canada. It’s a moment to remember Mennonite contributions and also consider ways of continued involvement, such as signing up to receive more information about MCC’s work in advocacy for displaced people, along with tools you can use to join us in this work. You can also download MCC’s Peace Sunday Packet for 2020, A Refugee People, for congregational resources for worship and reflection.

References:

[i] Canada Gazette June 1919, p. 3824.

[ii] Hildegard Martens, “Accommodation and Withdrawal: The Response of the Mennonites in Canada to World War II,” Social History/Histoire Sociale (November 1974), p 313.